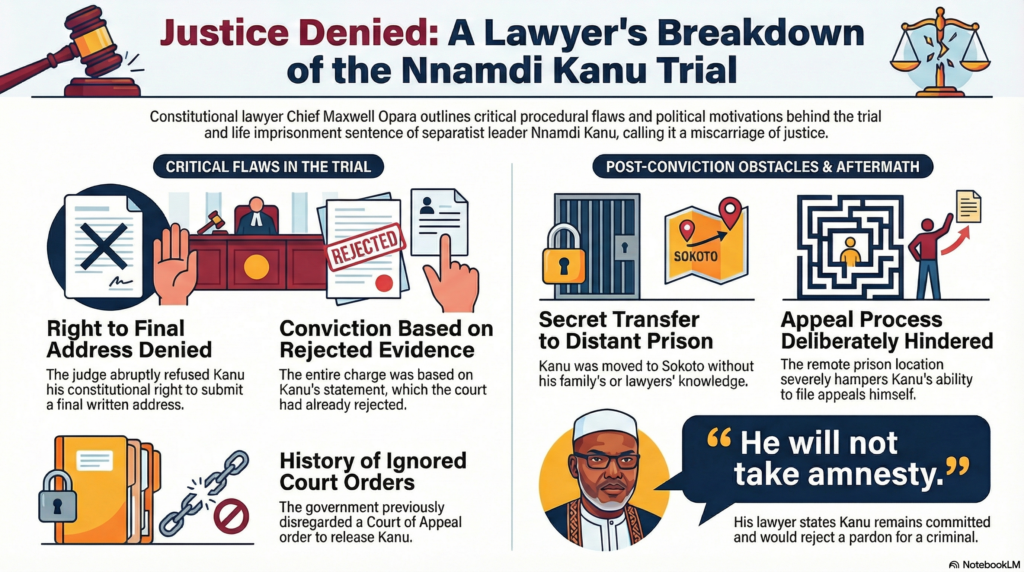

While the conviction of separatist leader Nnamdi Kanu marks a major legal endpoint, his counsel, Chief Maxwell Opara, alleges it was reached through a process riddled with “fundamentally flawed” legal maneuvers. Opara contends the trial was not a fair contest of evidence but a predetermined outcome, revealing a series of shocking procedural flaws that call the entire verdict into question. Here are the five most critical challenges to the judgment, drawn from his detailed account.

1. The Defendant Was Denied His Right to a Final Written Address

Chief Opara’s central claim is that the judge violated Kanu’s constitutional right to a fair hearing by abruptly refusing him the chance to submit a final written address. The significance of this denial was magnified tenfold by the judge’s own prior ruling: she had explicitly instructed the defense to reserve all objections to the prosecution’s evidence—particularly what Opara calls “doctored” and “cut and joined” video clips—for this final address, only to then foreclose the very opportunity she had mandated.

Opara described a dramatic scene in court where Kanu, representing himself, shouted, “Under what law are you shutting me out?” This final address was meant to be the critical moment for the defense to formally challenge the prosecution’s evidence and make its concluding case. By denying it, the court effectively silenced the defendant before delivering its judgment.

I have never seen that kind of crime in my life. Shut everybody in before our open eye and I join for judgment in a serious matter like this.

2. The Core Charge Was Based on a Statement the Court Itself Threw Out

According to Opara, the entire terrorism charge against Nnamdi Kanu was predicated on a statement he had allegedly made. To determine if this statement was admissible, the court conducted a “trial within a trial” to ascertain whether it was given voluntarily.

The outcome of this mini-trial was decisive. The judge was convinced that Kanu had made the statement under duress and issued a formal ruling to reject it, rendering it inadmissible as evidence. Opara argues a simple point of logic: if the foundational statement that supported the charge was thrown out by the court, the charge itself no longer had any legal basis to stand on.

…now that the statement has been rejected… which means [Kanu] has no statement, on what basis do you prefer the charge? Because you can’t put something on nothing.

3. The Government Previously Ignored a Direct Order to Free Kanu

Opara recounts a history of the government allegedly disregarding the judiciary. He points to a prior ruling by the Court of Appeal, Nigeria’s second-highest court, which had discharged Kanu and ordered that he should not be tried at all due to the “extraordinary rendition” that brought him back to Nigeria.

According to Opara, the federal government simply refused to obey this direct order. The case then went to the Supreme Court, which delivered a paradoxical ruling. While it validated the defense’s core complaints—criticizing the illegal rendition and the “Operation Python Dance” raid on Kanu’s home as “wrong”—yet, it ordered the trial to continue. Opara argues the government then engaged in selective obedience, ignoring the court’s scathing criticisms of its conduct while seizing upon the single directive that served its goal: to proceed with the prosecution at all costs.

Federal government look at court of appeal court of appeal You are talking rubbish We cannot obey it and they never obeyed it.

4. The Prosecution’s Exhibits Included Boxers, Singlets, and Perfume

In a capital terrorism case, the evidence presented is expected to be serious and directly relevant. Opara expresses bewilderment at the nature of the evidence, which he claims included mundane personal items like “boxers, singlets, shirts, [and] perfume,” and even a “knockout” firecracker—items he argues have no conceivable link to a capital terrorism charge.

His point is that a judge, in writing a final judgment, is supposed to review each piece of evidence and expunge anything inadmissible or irrelevant. By denying Kanu a final written address, the judge prevented him from formally challenging the relevance of these bizarre items. This issue was compounded by other evidence, such as video clips that Opara claims were “cut and joined” to remove exculpatory context—another key point Kanu had intended to deconstruct in his final argument.

5. Kanu Was Moved to a Distant Prison in Secret, Hindering His Ability to Appeal

Immediately following the conviction, Opara and Kanu’s family were not notified of his whereabouts. They later discovered he had been moved in secret via a “private presidential small jet” to a prison in Sokoto, a destination Kanu himself only learned of upon landing.

Opara argues this move critically obstructs justice. Because Kanu is representing himself, he is now “handicapped” and logistically unable to file the necessary appeal documents in Abuja, where the courts are located. With a 90-day window to file, this transfer creates a significant barrier. Opara notes the irony that while this move severely handicaps the appeal process, the location was justified by the court as a “secured place,” further complicating the defense’s ability to challenge the logistics.

Conclusion: A Question of Justice

From Chief Opara’s perspective, this was not a trial about evidence but a rushed, politically motivated process—what he calls “justice rush justice crush”—that systematically dismantled the defendant’s fundamental rights. The case, as he presents it, was less a pursuit of truth and more a demonstration of state power.

When the very architecture of a trial is challenged so fiercely—from the admissibility of evidence to the defendant’s right to be heard—what does it say about the health of justice itself?